Today's inflation cycle is the fastest and broadest in decades. Yet, it is misrepresented and misunderstood by policymakers and analysts. The inflation cycle has been in place longer than realized. Moreover, the cyclical uptick in inflation is more durable and will not end by merely ending the supply chain bottlenecks. The idea that producing more things and boosting economic growth will reverse the inflation cycle is nonsense. Inflation cycles end when monetary policy becomes restrictive, not before.

The New Inflation Cycle

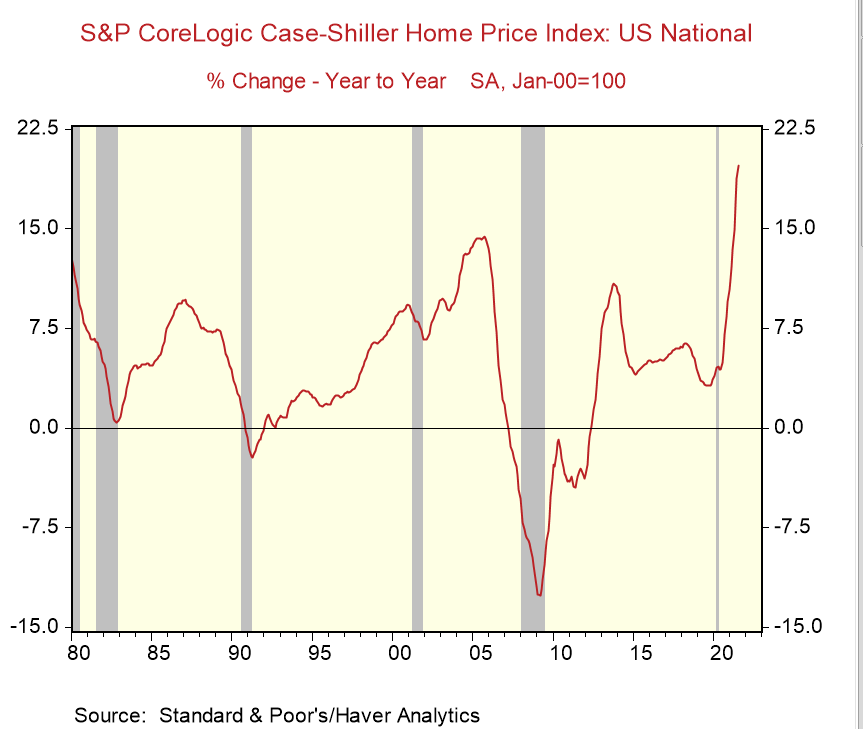

The initial signs of a new inflation cycle appeared in the housing market. In 2020, during the pandemic, house price prices rose 10%, according to the Case-Shiller. That was more than three times faster than the gain of the prior year and the most rapid increase since 2013. Some have argued that high and rising prices are self-correcting as buyers balk at the high prices. Yet, after increasing 10%, house prices posted a 15% increase, and the latest data shows a record 19.5% increase in the past year.

Housing inflation captures many elements of an inflation cycle. Easy money and credit conditions provide the fuel, and inflation expectations and speculation are also crucial drivers.

Politics and statistical issues have removed house prices from official price reports. Nevertheless, house prices still offer insight into experienced (or actual) inflation and inflation psychology.

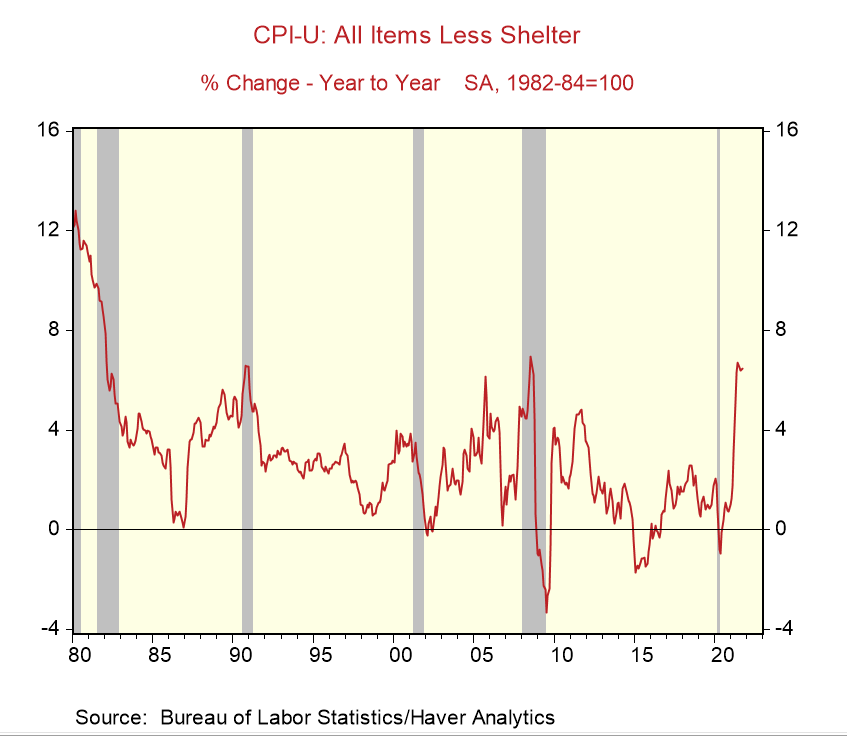

Including house prices in the official consumer inflation statistics would lift the reported figure to roughly 10% and rival the early 1980s. Still, excluding the non-market shelter index from the official price statistics shows consumer price inflation running as hot as it did during the oil price spike of 2008. Both represent the fastest increase since the early 1980s, illustrating the breadth and speed of the current inflation cycle.

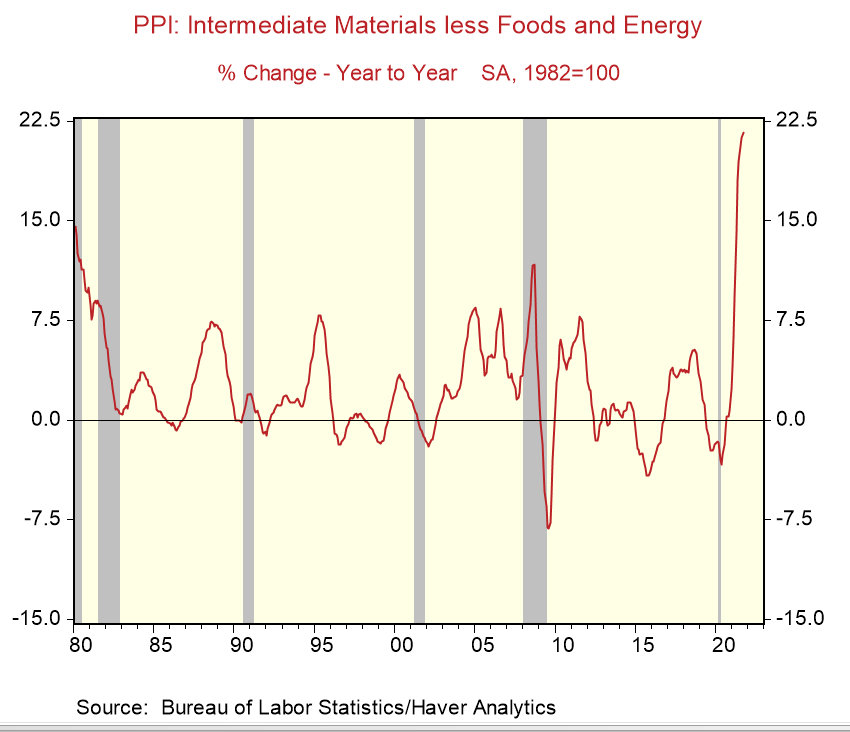

Other measures of inflation have already exceeded the reported figures of the early 1980s. Core intermediate prices for materials and supplies, which are part of the monthly producer price report, have jumped over 20%, well above the high readings of the 1980s.

The thinking by policymakers and analysts that eliminating supply-side bottlenecks will stop the inflation cycle is foolish. Producing more semiconductors will enable other manufacturers to increase the production of other goods and products, increasing the demand for materials and supplies and lift the demand for labor that is already in short supply.

In other words, increasing output and the growth rate of the economy does not end the inflation cycle; it merely changes the composition, raising the prices of some inputs (labor and materials ) and lowering the cost of others.

Policymakers initially misrepresented today's inflation cycle as they thought it was "transitory." Now it is misunderstood, which raises the risk of it becoming more permanent, resulting in more wrenching policy changes on interest rates at some point, with unavoidable adverse effects on the economy.

Comments