The Payback From QE---Fed Hikes Not Lifting Long Term Borrowing Costs To Break Inflation Cycle

- Joe Carson

- Mar 8, 2023

- 2 min read

The Fed looks at bond yields as a gauge of long-term inflation expectations and its overall policy stance. Policymakers believe moderate and stable long bond yields are consistent with well-anchored inflation expectations and an appropriately configured policy stance. Yet, questions surround the current signal from long-bond rates after a decade-plus-long program of debt security purchases (quantitative easing, known as QE) by the Federal Reserve.

Studies have shown that QE has lowered long bond yields by several hundred basis points. But, it needs to be clarified if the anchoring of long-bond interest rates via QE has also changed how the market price of long bonds adjusts to official rate hikes. Whatever the effect is, the Fed is not getting the market response it needs if it believes that higher borrowing costs are the main channel to break the inflation cycle.

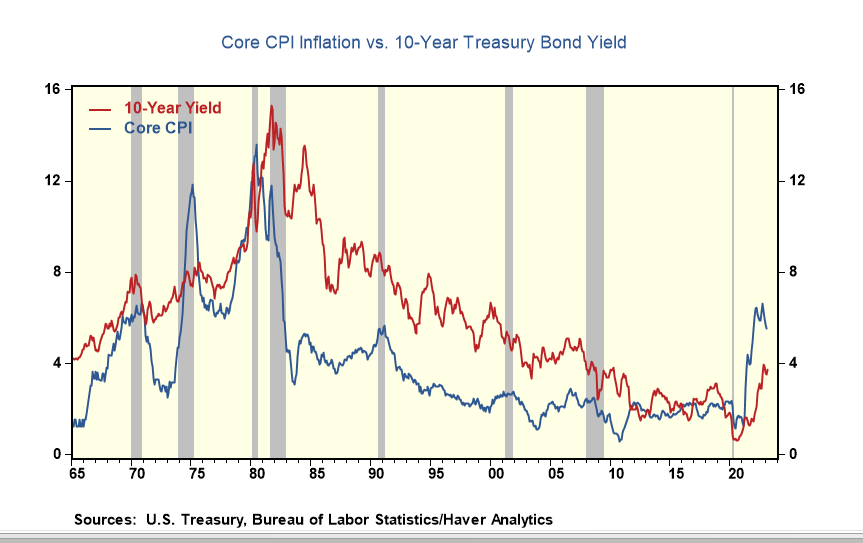

The core inflation and long bond yield picture that Fed faces today is something they have not encountered since the mid-1970s. One has to go back to the mid-1970s to find a similar alignment between long bond yields and inflation. The core inflation rate is approximately 200 basis points over the ten-year Treasuries yield, and that alignment has been in place for more than two years.

That alignment raises several issues, all pointing to higher official rates.

First, market rates adjusted for inflation have moved from "super" easy to still easy, indicating that the public's borrowing costs are still not sufficiently high enough to break the inflation cycle. That means the Fed has to hike official rates much more.

Second, an inverted Treasury yield curve with market borrowing costs below the inflation rate has never occurred before. If borrowing costs matter more, as history has shown, curve inversion does not have the same adverse economic consequences. Consequently, the Fed will need to raise official rates well above market expectations creating an even greater curve inversion to get the inflation slowdown its wants.

Third, the most significant risk to investors is if remnants of QE have permanently broken the links between long-term market borrowing rates and official rates. That would open the door to official rates moving to levels not seen in several decades. The risk of this scenario is low, but not zero, as the Fed has never faced an inflation cycle with QE in place.

Hi Joe, great read!

So if the Fed is not getting the result it needs/wants regarding long rates, why isn't it taking other steps to more directly affect higher long rates?

Why not more aggressively sell its holdings of longer-dated Treasuries? Or explicitly call out a target range or even a floor for long rates to be supported by its trading desk?

It is quite the conundrum for the Fed that the market is so firmly anchored in the view that longer term economic trends (ie demographics, productivity, etc) will keep economic growth potential and inflation very moderate long term (ie 10yr-30yr) and therefore resist the push of short term rates to pull up longer term rates.

I'm glad I…