Is A QE-Adjusted Yield Curve Inverted? It's Not, Confusing Investors and Complicating Policy

- Joe Carson

- Apr 4, 2023

- 2 min read

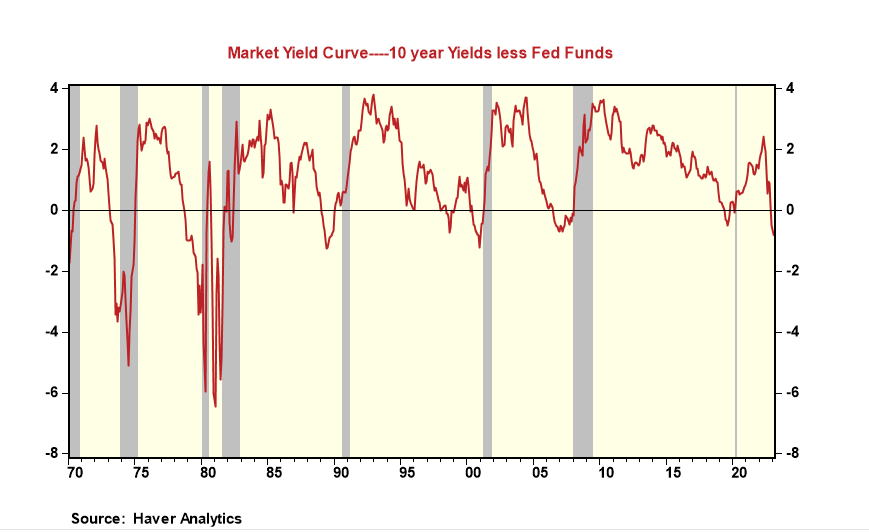

Is a QE-adjusted yield curve inverted? It's not. By lifting short-term rates over the past year and anchoring long rates with its new QE tool (quantitative easing), Fed policy creates an "unnatural" inverted yield curve. Nevertheless, if long-term yields remain below short-term rates, it will confuse investors and complicate monetary policy efforts to reverse inflationary pressures. But, importantly, since two conflicting monetary policy forces cause the inversion, there is reason to doubt its predicted outcome.

The Fed's primary tool is official interest rates. Since early 2022, the Fed has raised official rates by 475 basis points. That carries over point-to-point for increases in short-term Treasury rates, which measure one side of the Treasury yield curve.

After the Financial Crisis, the Fed created the quantitative easing tool enabling policymakers to continue injecting liquidity by purchasing marketable securities, mostly of longer duration. From the beginning of 2020, the Fed's balance sheet increased by nearly $5 trillion, from $ 4 trillion to a peak of $8.98 trillion in March 2022. It was reduced to around $8 trillion in March 2023, which is still twice what it was at the start of 2020.

QE creates an anchoring effect on long-term interest rates, the other side of the Treasury yield curve. Several studies have estimated that the scale of the QE is the equivalent of a 200 to 300 basis reduction in the Fed funds rate.

So is the QE-adjusted yield curve inverted? If the yield curve is measured from fed funds to 10 years, it's not because the effects of QE cuts the current target range of 4.75% to 5% in the federal funds rate in half.

That helps explain why equity prices continue to rise, company profit margins remain near record high, and labor markets remain robust and tight. If the market yield curve signal were an accurate gauge of what was occurring nowadays, we would see the flip side of those economic and financial conditions: a wide range of companies posting operating losses, millions of people losing jobs, and equity investors losing money.

What does the "unnatural" yield curve inversion mean for Fed policy? Whatever policymakers thought was the terminal rate for fed funds to quell inflation, they should add 200 to 300 basis points. That sounds like a far-out guestimate of fed funds, but that's the flip-side or negative consequences of QE---in other words, given the scale of QE, it requires a higher level of official rates to generate the monetary tightening needed to rein in inflation.

Comments